The fi rst proper civilization is generally referred to as Sumer, which encompassed a few dozen cities, including Lagash, Umma, Uruk, and Ur—all of which are in modern-day Iraq. These people practiced year-round agriculture, created complex irrigation systems, and practiced monoculture, which involves growing single crops intensively.

The first recorded recipes were found in these cities, which began to flourish around 4000 to 3500 B.C. In this lecture, you will learn that a civilization blessed with great fertility and natural boundaries, combined with court patronage from the top, is bound to develop a complex cuisine that will last for millennia.

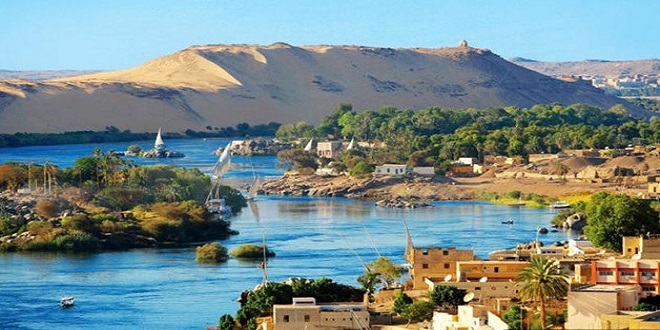

Ancient Egypt

Egypt is the fi rst place to have a fully developed, socially stratified civilization outside the Fertile Crescent. The agricultural revolution was imported there, and it’s the first place that we have full documentary as well as archaeological evidence of agriculture, domestication, cuisine, and medicine.

There is evidence of extensive writings as well as paintings of foodstuffs; therefore, we can talk about the history of food there. We also have tons of physical evidence courtesy of the hundreds of preserved Egyptians—mummies—with whom there was often entombed jars of food.

The Egyptian Diet

Every visitor in classical times remarked how fertile Egypt was and how much grain they had. The state stored massive amounts of grain to prevent famine in lean years, as in the story of Joseph. They often imported grain from Syria or demanded it in tribute from subject states. The state usually distributed this grain as a kind of welfare system administered by the priests, who perhaps 23 first offered it to the gods and then redistributed it. There is also evidence that grain could be used for taxation purposes.

Egyptian Beer

Sophisticated archaeological techniques that have been developed in the past few decades have allowed researchers not only to identify vessels that stored beer in ancient times, but they also can identify exact ingredients as well. Patrick McGovern at the University of Pennsylvania is the best-known bimolecular archaeologist of ancient drinks, and he has even worked with breweries to develop modern versions.

Although they taste quite good, they use modern strains of yeast and brewing protocols that are very different from ancient practice. These are the dictates of modern regulations and the demands of commerce—but at home, you can brew exactly as the ancients did, using wild yeast and simple pottery vessels. Be prepared, though, it will not taste like your standard fizzy lager.

Turn them around every now and then, drain off the liquid, and replace it if it begins to smell a bit. They should stay moist during germination. This should only take a few days. Once you see them sprout, dry them off, and place them in the sun to dry completely. If you want a darker brew, toast a few of the grains gently and add to the rest. Then, break everything up in a large mortar. You want small pieces, but not powder.

Last word

Next, heat the grain in water at about 140 degrees, and maintain that temperature for an hour. Strain this into another pot, and pour some more hot water over just to release the last bit of sugars in the mash.

Now is the fun part. Cover the pot with a cheesecloth, and let it ferment at room temperature. Wild yeasts will invade, and it will start to bubble in a few days. Taste it periodically; it will probably be a little sour, thick, and of course still room temperature. That’s ancient beer—fairly low in alcohol but refreshing. If you insist, strain it again, funnel into bottles, and refrigerate.